The Sonic Image

Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Through the walls of Boris Johnson’s London apartment leaked out the sounds of a domestic altercation with his partner Carrie Symonds. In a statement given to the police, his neighbour and witness to the incident said:

“It became clear that the shouting was coming from a neighbour’s flat. It was loud enough and angry enough that I felt frightened and concerned for the welfare of those involved. After a loud scream and banging, followed by silence, I ran upstairs, and with my wife agreed that we should check on our neighbours.”

Johnson’s defenders and employees of Rupert Murdoch accused this witness of being a “curtain twitcher”, a slur reserved for an eyewitness, one who intentionally peers and directs their gaze at an incident out of an unwarranted curiosity. The witness in this case, however, is not an eyewitness but an earwitness. Rather than violating the privacy of another, the earwitness, in this case, has his own private space invaded with the acoustic incidents of his neighbours. In terms of acoustic space at that moment of violent amplitude the witness and suspect occupied a shared space, they were in one space together despite the division of rooms that visually separate the space. In turning this witness from ear to eye the press falsely assign both intention and debasement of the evidentiary value of his testimony. This is just one example of a display of vested interest in the erroneous applying of visual logic, visual space onto the sonic. All too often, especially in the realm of evidence, sound is treated as an image, to be more specific as a poor image. But what I want to talk about today is that rather than this configuration of sound to image, the inverse is at stake. That is, using the sonic imagination to trouble the image. Rather than sounds being forced to behave in the logic of the image, how can an image behave like a sound? What is politically at stake in making and seeing images that leak through and beyond their sensory and spatial frame? It is not often that I am asked to speak about images and so I want to use this occasion to show two examples of how I have tried in my own work as a visual artist to negotiate the sonic image. Putting one of my more well-known earlier works from 2012 side by side with something that I am developing now, we can see how the sonic image became necessary to establish new ways by which claims can be made and formerly silenced testimony heard.

In the year 2000, there was a total of fifteen fortified border walls and fences between sovereign nations. Today, physical barriers at sixty-three borders divide nations across four continents. This huge increase in the fortification of borders over the last seventeen years has not only consisted of razor wire and concrete but also in the so-called immaterial and biometric strategies, including the forensic analyses of migrant voices. Immigration authorities around the world turned to forensic speech analysis to determine if the accents of asylum seekers correlated with their claimed national origins to see whether people originated from areas perceived to be dangerous enough for them to legitimately claim asylum. Borders were thus intuited and constructed within the voice itself. This process, called “Language Analysis for the Determination of Origin” (LADO), was first implemented in 2003. LADO uses its capacities to supposedly derive the truth of an utterance to help determine the validity of asylum claims made by tens of thousands of people without identity documents in Australia, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

LADO is mostly conducted by one of two private companies run by forensic phoneticians based in Sweden: Sprakab and Verified. LADO reports are achieved by soliciting the speech of the claimant via a telephone interview organised between the asylum seeker and an anonymised listener hired by one of the two aforementioned companies. These ‘listeners’ are former refugees, now Swedish citizens, that originate from the countries or neighbouring countries of those who are claiming asylum.

These people are tasked with making a series of assertions about where they believe the asylum seeker ‘really’ comes from. These unscientific assumptions are reworked into reports by linguists to bolster the claims of the anonymised former refugee analysts with international phonetic symbols and a lexical variety befitting a forensic or expert report for use in asylums tribunals all over the Western world.

An accent should not be understood as a pronouncement of place of origin, but rather as equivalent to layers of metadata. Accent is an indication of the voice as network, a network with nodes in various places, times and identities. An accent is formed through and in communication with others; it is relational, in the sense that we hear not only the speaking subject but traces of their past and present interlocutors. The voice has a tendency to mimic the accents of those it speaks and relates to so that the sound of an accent is possessed to some degree by every person it has come into contact with. When the accent is heard as a network and not a birth certificate, we hear it as a biography of migration, as an irregular and itinerant concoction of contagiously accumulated voices, rather than as an immediately distinguishable sound that avows its defined roots within the confines of a nation-state. Such irregularities should provide proof of the applicant’s need for asylum and stability. But instead, the sounds of vocal migration, which have the sonic quality of geographic irregularity, are cited as grounds for refusal of asylum applications, as LADO promotes a system of vocal governance that deems speakers with mixed and multiple accents as dishonest. Yet in the governance of accents, the border is a visual demarcation that dissects a sonic plane. And in these images, I am trying specifically to invert that, to show that sounds can not be so easily dissected by the colonisers’ cartographic rulers and pens. It is through this sonic image that I propose strategies for mapping the voice that are more faithful to the way the medium bleeds through histories, bodies and borders. The attempt here is not only to render an image of a sound but rather to create an image that behaves like sound itself.

© Lawrence Abu Hamdan

This next example of a “sonic image”, has nothing to do with sound, and that’s why I want to show it. I want to see if the idea of the sonic image itself can leak past its own disciplinary boundaries to form a generalised relation to the image that is not specifically dedicated to capturing sounds leaking through borders or walls. Can it be used to make visible distinct ways in which memories leak through time and subjectivities?

© Lawrence Abu Hamdan

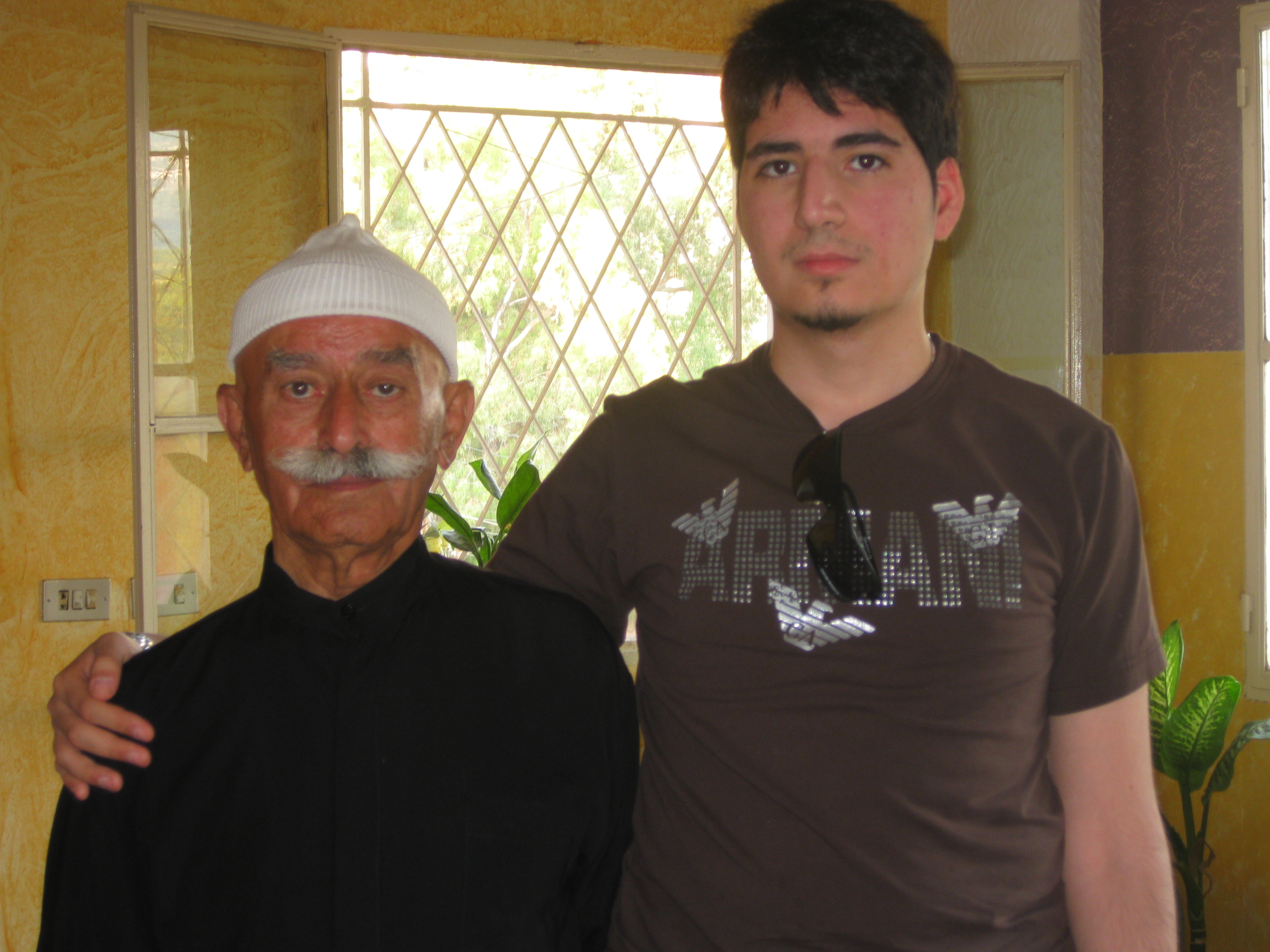

Bassel is the son of my cousin’s cousin. He is roughly my age but believes himself to be the reincarnation of Yousef al Jowhary, a child soldier who died at 16 during the 1984 Chouf War in Bhamdoun. This is one of the most unspoken and unresolved parts of the history of the Lebanese civil war because it is a moment when villages that had largely co-existed for around a thousand years tore each other apart. Bassel’s reincarnation is not unusual in that is born to a religious community that believes in Reincarnation. This same community made up the majority of the militia of the Progressive Socialist Party for which Bassel fought in his past life. In the context of this presentation on the politics of the sonic image, I will be unfolding but one strand of many in Bassel’s story, one that particularly refers to Bassel’s search for his own image.

Bassel’s flashbacks to a time in which he did not himself live have compelled him to become an obsessive auto-didactic historian, a young man pushed to find traces of his own existence. He’s used his reincarnation to amass not only information on his own life but the largest archive of photography, weaponry, uniforms, flags and badges of the Chouf war, and the entire militia of the Progressive Socialist Party.

Bassel has now become a historical resource, he holds vital information for anyone hoping to understand the historical record of a time which has been cancelled from history.

Bassel began by collecting martyrs’ posters from that period, hoping to find a correct record of his own death and an image of who he used to be.

Through a family contact, Bassel connected with one of the militia’s key graphic designers and poster printers. The now-elderly designer gave Bassel free rein amongst his disordered remnants. Amid the old defective prints, flags and never-released designs he eventually found one in which Youssef’s name appeared.

The space where his image would normally appear was blank. Bassel left the designer’s house not just with this poster, but with as many of the half discarded posters, flags and badges as he could carry.

© Lawrence Abu Hamdan

Bassel still sought to procure his own image. Up to that point, he had avoided exactly what would lead him to it; his parents from his past life. Inevitably, one day Bassel knocked on the door of the Jawhary family home in Bhamdoun. His former sister opened. Bassel announced who he was and who he had been and he was quickly welcomed inside. The elderly man sitting on the balcony, Fouad al Jawhary, Youssef’s father, rose to shake his hand. Fouad gave him the uniforms Youssef wore during the war, including the one in which he had died, and the rifle he had used. When Bassel inquired if there was a photograph he could have, Fouad, his former father, explained that the only existing image they had of Youssef was an out of focus black and white image taken when he was six years old, adding that, Youssef hated having his picture taken.

Thinking that maybe his ex comrades from the war in Aley might have a picture of Youssef, Bassel began to locate and interview whomsoever he had known. This is how he began accessing and archiving personal photographs and collecting memorabilia of many ex-fighters across Lebanon.

Starting with people that had fought or trained with Youssef and then the people who had fought and trained with those people, and then people who had fought and trained with those people and so on and so forth, Bassel created a network across the mountains of ex-fighters and their family members.

Bassel’s reincarnation has given him access.

His reincarnation and his research are inseparable. If an ordinary, bonafide university historian were to show up at these houses asking for such documents, they would be told that none exist.

But as a returned fallen comrade, Bassel is treated differently.

Amongst the community of those who believe in reincarnation he is, after some explaining, welcomed to examine, then eventually, archive much of this material.

Bassel is in a unique position to traverse a silence that spans two generations. One is silenced by the necessity and responsibility to avoid stirring up a sectarian past in which they fought, whilst the other, my generation, is silenced by the absence of historical teaching and cognisance of the war. In this way, his testimony, whether learnt or unlearnt, whether planted or transmigrated, make formerly impossible speech possible.

Bassel still has very little idea of what he looked like in his previous life. He may have an image of Yousef in his vast archive but without knowing what he looked like, he cannot identify himself. With the idea that we could try to see if indeed such a picture exists amongst Bassel’s collection, I approached Dr Caroline Wilkinson at Face Lab, a research group at Liverpool’s John Moores University that carries out forensic/archaeological research, including craniofacial analysis and facial synthesis. I asked her if she could use the image of Youssef as a six-year-old child (as well as reference images of his brother and father) and reconstruct what he may have looked like at 16-years-old. This was the result.

The process she used to create this image is often used in missing persons cases, particularly when someone goes missing as a child. She explained to me that she has had astonishing results. Most recently, she produced a facial synthesis of a woman from her skull alone. By circulating this image to the public, an old neighbour identified that reconstruction as someone who she had known and who had disappeared many years prior. This is how the police were able to identify the body.

Dr Wilkinson explained to me that her success in such cases depends on staying within a tight threshold of recognition, the face has to be both specific enough to elicit the memories of those who have seen the face before while also generic enough not to overstate any one specific characteristic, for fear of throwing people off the trail of identifying them. You need to open and activate the interpretive capacities of the viewer. To do this, the faces also have to be somewhat digital, there must be enough digital artefacts, like this intentional pixelation she has placed in the background, to be able to tell that this is indeed an illustration and not a real photograph. For if it is too real, people will not be able to interpret the image as a reference instead of a real portrait.

At the same time, the face cannot be completely digitally rendered, as Dr Wilkinson needs the public to see this face as believably human to solicit an urgency to their gaze. To keep this human threshold, she must use real human facial features. Each of the features that make up this image is cut and copied out of anthropological archives and photographic databases. To make her database, Wilkinson collects endless portrait books, including titles such as Berbers of Africa, Faces of the ZULU, The Atlas of Beauty: Women of the World in 500 Portraits, Crowns: Portraits of Black Women in Church Hats, The Photographer's Guide to Posing, Techniques to Flatter Everyone, The Moment It Clicks, Tibetan Portraits. From these books, she harvests eyebrows, hairlines, noses, eyes, mouths, chins, facial hair and skin textures. She then intentionally erases the source of these images so that they become a sea of unidentified stray features floating away from the faces to which they were originally attached. She does this to limit her own cognitive racial bias and focuses only on the distinct feature she feels would best fit the face she is reconstructing. She also creates this massive mix so that she will not be tempted to use too many features from one single face, or she risks recreating an incident from a 2011 FBI investigation. During their search for Osama Bin Laden, the FBI released to the public an image of a synthesised, older looking Bin Laden. But in doing so, they used too much of the face of Spanish Politician Gaspar Llamazares. Many Spaniards recognised Llamazares in the face of Bin Laden, forcing the FBI to retract the image and apologise after Llamazares became enraged. For Wilkinson, this became a lesson to choose each feature separately. To compose Youssef’s face, Wilkinson must look through her unaccounted catalogue of features before fixing on the faces of eight people that constitute this one face. His eyes were chosen because, at a young age, he seemed already to have eyes which sat shallow in their sockets, eyes where the lids protruded. Only the lips were significantly altered in photoshop, puffed up a little to match the development of lips in his family.

The memories that are lodged in Bassel’s mind are not a product of empathy for the trauma suffered by the generation which preceded him, for empathy suggests Otherness. It is not that he can feel another individual’s pain but that through reincarnation, individuality itself becomes undermined. That is why this face made of many nameless faces is somehow, for me, not the perfect portrait of Yousef but perhaps the perfect portrait of the new category of witness that reincarnated testimony produces. They are witnesses who leak into other bodies, who bleed across generational and potentially sectarian divides, forcing new pathways to the production of history that have otherwise been sealed.

But why is this a sonic image? Because an image behaves like a sound when its true value is derived out of its relational rather than individual qualities.

The material conditions of sound make it an inherently difficult article of evidence as it can not be isolated often from the space in which it resounds. Sound waves, unlike photons of light, do not themselves move through the medium but cause a rippling effect that creates a rapid series of movement of the molecules around them; the object of sound is not itself moving but instead, it is causing movement. The vibration of sound is therefore a collaboration between molecules of distinct objects, which is why analysing sound is a challenge to how evidentiary fragments are conventionally managed. Sound and sonic imagination, therefore, act as new propositions for soliciting evidence and in turn for producing and reading images that are continuous with the omnidirectional and uncontainable way that sound propagates throughout the space of a building, the border of a nation and through the architecture of memory itself.

At stake in the sonic image is an end to isolationist practices. An end to an ideology of monolingualism and binary forms of identitarianism. I have tried to show when the logic of acoustic inseparability is applied to image production counter forms of testimony can be made audible. An image that behaves sonically can become a medium for truths to emerge that are impossible in a world in which our listening to testimony is still governed by the tight confines of the visual image.